An international team of scientists, including from Memorial University, has taken a major step in deep-sea exploration by sampling Earth’s last truly remote and inaccessible seafloor environment: the depths of the Arctic Ocean.

This fall, Dr. John Jamieson, an associate professor of earth sciences and the Canada Research Chair in Marine Geology, was part of an expedition that was the first to dive to a hydrothermal vent field under the polar ice cap.

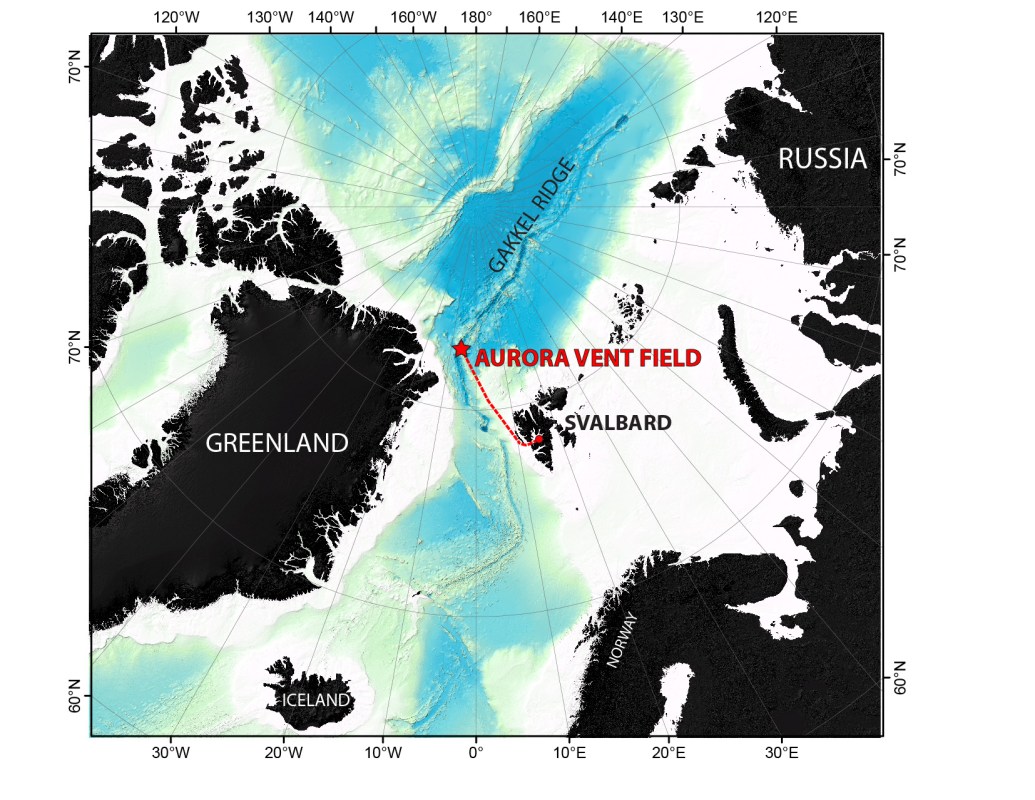

Hydrothermal vents have been found in all ocean basins, but little is known about hydrothermal venting in the Arctic Ocean. The Aurora vent field, an approximately four kilometre deep hydrothermal vent field at 82.5° N, was discovered north of Greenland in 2001.

‘Significant leap forward’

“Despite several attempts, researchers have been unable to directly explore, image and collect samples from this vent field, due to the extremely challenging conditions of deep-sea exploration under the Arctic ice cap,” said Dr. Jamieson. “That is, until now.”

Hydrothermal vent fields are clusters of high-temperature (over 300°C) fluid hot springs that occur on volcanically active parts of the sea floor. They are also called “black smokers” because they emit thick plumes of black smoke. The vents host accumulations of potentially valuable metal-rich minerals and unique ecosystems that rely on the chemical energy from the hot fluids as energy sources.

Using a remotely operated vehicle, also called Aurora, the team successfully collected more than 100 rock, fluid and biological samples from the Aurora vents.

“This represents a significant leap forward in our abilities to study the geology and seafloor ecology of the Arctic Ocean, which until now had remained largely elusive,” said Dr. Jamieson.

The HACON21 expedition, which took place aboard the Norwegian research icebreaker Kronprins Haakon, was a multi-institutional project led by researchers at the University of Tromsø, the Norwegian Institute for Water Research and REV Ocean.

1/

Dr. Jamieson on the helicopter deck of the Norwegian research icebreaker R/VKronprins Haakon.

2/

Dr. Jamieson and fellow researchers removing rock samples collected from the 4 km deep Aurora vent field and brought back to the ship using the REV Ocean remotely operated vehicle (also called Aurora).

3/

Aerial view of the R/V Kronprins Haakon as it cuts through polar ice, 425 nautical miles from the North Pole.

4/

The multi-disciplinary science team included representatives from 8 research institutions in 7 countries.

5/

The 27 day cruise departed from Longyearbyen, Svalbard to study the Aurora vent field, located at the western edge of the Gakkel Ridge, a 2000 km volcanic ridge located entirely beneath multi-year polar ice.

6/

Black smoke emitted from “Enceladus,” a high temperature vent discovered within the Aurora vent field and named after the Saturnian Moon of the same name that hosts an ice-covered ocean thought to also contain hydrothermal vents.

7/

Dr. Jamieson displaying a piece of chalcopyrite, a copper-rich mineral that forms the interior lining of hydrothermal vents.

Worldwide team

The team of 28 multidisciplinary scientists also included researchers from the University of Bergen; the Institute of Marine Research, Norway; University of Aveiro, Portugal; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, U.S.; the Alfred Wegner Institute, Germany; the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, U.S.; and the University of Southampton, U.K.

They left Longyearbyen, Svalbard, on Sept. 27 and returned on Oct. 24.

“My role in the project focused on the collection and characterization of the mineral deposits forming at Aurora,” said Dr. Jamieson. “I was invited to join the group due to my expertise studying the geology of these types of systems, as well as a long-standing collaboration with researchers at the University of Bergen.”

Samples collected during the expedition were sent to Memorial, where they will be examined and analyzed to characterize their mineralogical and geochemical compositions.

“We will also measure the concentrations of different radioisotopes within the samples to calculate the ages of the samples and thus the age, history and evolution of the vent field,” said Dr. Jamieson. “Our success in this expedition was due to a combination of hard work, very careful planning, a healthy amount of luck, learning from previous attempts and a great group of scientists, ROV pilots and ship’s crew that worked together to make this success possible.”

A key goal going forward is to use the results to work together on challenges and solutions related to Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems and Marine Protected Areas. This will result in new science provided to intergovernmental initiatives such as the United Nations’ conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the United Nations Decade for Ocean Science.